Why Watch Prices Are Plummeting – The Fall of the Luxury Watch Market

By Scottish Clans on Jan 01, 1970

The past few years in the watch market have been nothing short of a roller coaster. Certain “hype” models saw astonishing surges in the secondary market, often trading for multiples of their original retail price. In the spring of 2022, for instance, the Rolex Daytona 116500LN commanded around $49,183, the Patek Philippe Nautilus 5711 soared to $177,700, and the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak 15500ST reached $118,407. Fast forward just two years, and these same models and many others have experienced significant drops in value. Let’s explore why watch prices fluctuate and what has triggered the recent downturn.

Introduction

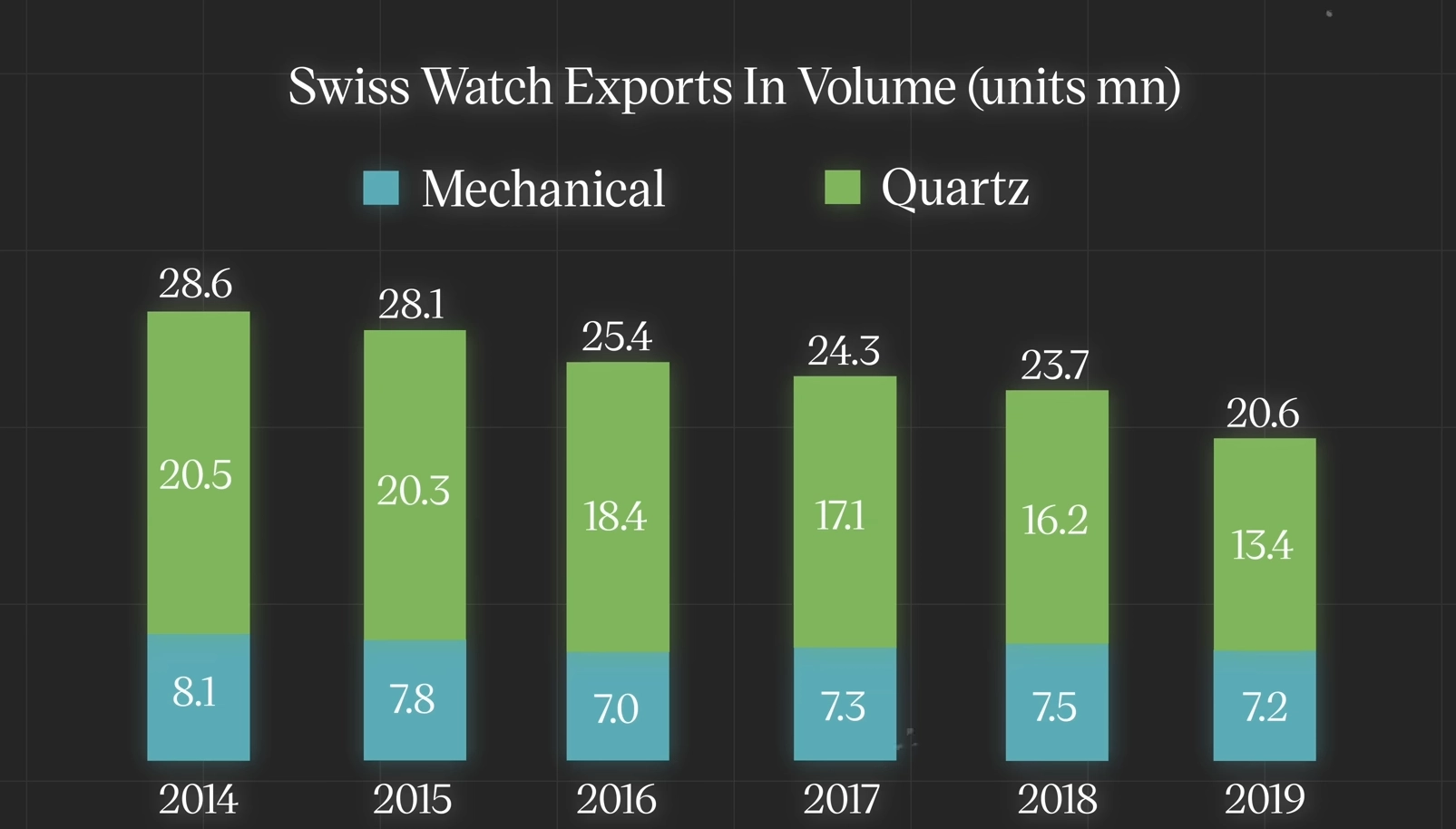

Since the rise and popularization of smartphones, you could argue that owning a mechanical watch, or any watch in general, is no longer a necessary tool for everyday life. Yet, despite this, mechanical and especially luxury watches have been relatively steady. If you look at the broader concept of Swiss exports, it does tell a bleak story for affordable quartz watch production, with total Swiss watch exports dropping from 28.6 million in 2014 down to 20.6 million in 2019, a drop of nearly 30%. But as you shift over to mechanical watches, you will notice that the market has not seen the collapse that you might expect in this period. You do see roughly an 11% drop in production, mostly as a byproduct of the more attainable end.

In recent years, it has become clear that mechanical and high-end watches have taken on a new meaning for buyers. While utility still exists, it is no longer the primary reason for a purchase. Unlike fast-moving electronics that are quickly outdated, a mechanical watch exists in a world removed from constant technological churn. This shift has transformed watches from purely functional tools into collectible works of art, expressions of personal style, and symbols of status qualities that smartwatches simply cannot replicate.

The numbers support this trend. Brands like Rolex, Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin, Patek Philippe, Richard Mille, and FP Journe have seen unprecedented demand. This redefinition sparked a fascination with collecting, where hype quickly followed certain pieces, turning them into “hero” models that transcended the niche collector market and captured widespread appeal.

The influence of Paul Newman

If we had to identify the tipping point for when the collector world collided with the broader public with just a moderate interest in watches, it would be back in 2017 when Paul Newman’s personal 6239 Daytona sold for $17.8 million at auction. This number was absolutely staggering and enough to grab the attention of the press and those outside of the watch-buying circles, giving rise to a different type of collector that was driven by chasing the exclusive, all while the old-school collectors remained captivated.

This frenzy at the top soon trickled down to new product releases. Select brands many of which operated privately saw unprecedented interest in their watches at retail, giving rise to waitlists. The private nature of these brands was crucial, as they could take the long view without the pressure to overproduce for shareholder returns, unlike publicly traded companies. This is why names like Rolex, Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Richard Mille experienced such explosive demand during this period.

The surge in demand created a perfect storm. As watches became harder to obtain, they grew even more desirable among luxury buyers, driven by the allure of owning something exclusive. At the same time, markets like China experienced a boom, fueled by rising wealth and rapid boutique expansion. For example, Rolex alone now has over 160 points of sale across China, further fueling global demand.

Flipping Culture

This environment gave rise to a flipping and dealing culture. If you were fortunate enough to snag a watch at retail, its value could skyrocket the moment you walked out the door. Many buyers succumbed to the temptation of selling to dealers, and some questionable practices began to emerge, including secondary market dealers hoarding inventory of high-demand models.

As watches became increasingly difficult to obtain, authorized dealers (ADs) could no longer display them openly, since new arrivals were often already claimed. This led to a game of navigating waitlists, and in some cases, less scrupulous ADs maximized profits by selling directly to secondary market dealers at prices closer to trading values rather than retail.

And just as it seemed like it couldn’t get any more out of control, 2020 came around and the lockdowns kicked off a very complicated time for the watch industry. On one hand, it was disastrous in the early months as points of sale needed to be closed. In this industry, there are brands like Rolex that do not allow authorized retailers to sell online. Therefore, when lockdowns happened, it meant brands were essentially closed for business.

Production

Back at the factories overseas, you also had another issue that was brewing. As many of you probably already know, producing a watch that comprises hundreds of parts is not an easy manufacturing process to streamline, requiring a meticulous order of operation to ensure numbers and quality are met.

The accepted industry terms for assembly are as follows:

- T0: The pre-assembly of smaller components of a movement.

- T1: The assembly of the movement and final adjustments.

- T2: The adding of the hands and the casing of a watch.

- T3: The attachment of bracelets or straps and preparing the final presentation box.

Most watchmakers or technicians at major brands specialize in a specific stage of assembly rather than handling every step independently. While smaller-scale or bespoke productions sometimes have a single watchmaker complete an entire piece, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in this model. Social distancing and illness caused major disruptions on production lines if one step was delayed or a unit failed, it could hold up production across the entire brand.

Compounding the issue, the shipment of raw materials and specialized parts, such as hairsprings, dials, and cases was severely disrupted, especially when shipments crossed international borders. The combination of highly specialized workers who needed close collaboration and difficulties sourcing critical components created a perfect storm for slowed production.

The data reflects this impact clearly. Swiss watch exports fell from 20.6 million units in 2019 to just 13.8 million in 2020 a roughly 33% drop in a single year, one of the largest declines in industry history. While this could have been catastrophic, it had some unexpected effects.

Global markets were facing uncertainty, prompting governments to inject liquidity through stimulus checks, lower interest rates, and quantitative easing. With travel and leisure severely restricted, many consumers redirected discretionary spending toward collectibles, including watches. This surge of available cash intensified pre-existing waitlists, as buyers with means were willing to pay well above retail to secure the pieces they wanted.

Market Liquidity

To provide a sense of what was taking place with the growing snowball of consumerism, a term coined by the 19th-century economist named Thorstein Veblen, it is defined as the expenditure on or consumption of luxuries on a lavish scale in an attempt to enhance one’s prestige. Following this research, it later unearthed that certain types of goods countered the simple rules of supply and demand.

In a typical scenario, goods that increase in price within the open market typically see a downturn in demand once prices reach a point beyond what buyers are willing to pay. However, in luxury goods, where consumer behavior is much different and need is not the same or even part of the equation altogether, there is a rare phenomenon that can take place where goods that see their prices go up can also see their demand rise, given that the difficulty to obtain is seen as a way to elevate status. This rare circumstance classifies these types of products as Veblen goods, and in this time of 2020 to 2022, watch collecting is one of the best examples of this concept in recent economics.

To add fuel to the fire were individuals on the outside who were looking at the increasing trading market values and saw this as an opportunity to increase their portfolio of wealth, thinking watches could become an investment vehicle. The attention at this point was mostly being directed towards the “big four.” However, the focus on these brands led to others beginning to succeed. An example of this is a brand like Vacheron Constantin with their Overseas models, specifically the blue dial Overseas that peaked in April of 2022 at a trading value of $49,917, a number that doubled their retail price at the time.

Yet, since people struggled to get allocation for the Nautilus and Royal Oak, buyers were looking elsewhere, with this same effect taking place in countless other scenarios of alternatives.

It was a completely unprecedented situation, and as the secondary market sustained, we had brands that were basically printing money, since as soon as they prepared a watch for sale they had a line of customers ready to buy for nearly every model. The secondary market peaked in the early spring of 2022 and positive momentum seemed never-ending, however as we know now, things were about to change.

According to the WatchCharts Watch Index, which takes the trading value of 60 watches taken from the top 10 luxury watch brands, sorted by transaction value, it shows that the secondary market has dropped over 36% since March 2022.

Sudden Drop

This growth, however, was unsustainable. Publicly traded companies like Watches of Switzerland Group PLC, which operate numerous authorized dealerships, saw their stock prices fall more than 60% from all-time highs in late 2021. By spring 2022, the luxury watch bubble had burst.

Key factors driving the downturn included:

-

Rising interest rates: Increased borrowing costs reduced disposable income for luxury purchases.

-

The war in Ukraine: Geopolitical instability dented consumer confidence.

-

The cryptocurrency crash: Many buyers who had invested in watches with crypto lost substantial wealth.

-

Chinese lockdowns: Restrictions disrupted one of the largest global markets for luxury watches.

These factors, coupled with an overheated market, caused secondary market prices to plummet. Buyers who had purchased watches at inflated prices were left unable to sell for a profit.

What This Means

The decline does not signal the death of the luxury watch market. Demand remains strong, though less frenzied, and prices are expected to stabilize at more sustainable levels, driven by genuine collectors and enthusiasts.

For those who value the craftsmanship and aesthetics of a Rolex without engaging in the volatile collector’s market, high-quality replicas and superclones offer an attractive alternative. These watches meticulously replicate the look and feel of the originals, providing the prestige and beauty of a luxury timepiece without inflated prices, stressful waitlists, or the financial risks of market fluctuations.

The recent collapse of the watch market bubble is a reminder that no market can rise indefinitely. It underscores the importance of caution when making large purchases, particularly during periods of economic uncertainty, while highlighting that the appreciation for fine timepieces can exist independently of market hype.